Traditional Italian food is very regionalized, as Italy was unified only in the 19th century. As a result, the cuisine of each province was based on local ingredients, history, and traditions. Here is a synopsis of each region, starting with the ones that shaped and influenced most of the Italian cuisine we know today. Find for each region the most common dishes and some of the recipes.

Going back to the Roman Empire, wealthy Italians have always enjoyed lavish banquets.

Still, while the rich could access the most expensive and refined produce and meat, the rest of the Italians had to eat whatever was available.

The same happened throughout the centuries, with the Popes and aristocrats accessing the best main ingredients and leaving everybody else with the rest.

Luckily, the Mediterranean climate produces an incredible variety of fruits and vegetables.

Therefore even the poor could make excellent dishes substituting animal proteins with cheese, pulses, and cheap cuts of meat.

In "la cucina povera," nothing gets wasted!

As long as you have fresh, local seasonal ingredients, you can make wonders!

This is the basic principle of Italian cuisine, whatever the region.

To find out more how Italian food tradition changed throughout history you can read the article: Italian food history and cultural influence.

Jump to:

- Italian biodiversity

- Northern versus Southern Italian cuisine

- Regional variations versus worldwide variations

- The first Italian recipe book

- A historical look at Italian regional cuisine

- Tuscany

- Emilia Romagna

- Veneto

- Piemonte

- Val d'Aosta

- Friuli Venezia Giulia

- Trentino Alto Adige

- Lombardia

- Liguria

- Sardegna

- Umbria

- Lazio

- Abruzzo

- Molise

- Marche

- Campania

- Basilicata

- Puglia

- Calabria

- Sicily

- More authentic Italian resources

Italian biodiversity

A speech from Oscar Farinetti, the founder of Eataly, perfectly describes the unique Italian position regarding food.

It is called The Luck of the Italian.

"Italy is the only peninsula that travels tightly from north to south on a perfect latitude enclosed within a good sea, the only geographical situation on the planet, so it happens that the good winds of our seas meet with the good winds of our hills and our mountains and it is unique in the world…"

"….. in this small space that represents 0.5% of the surface of the world, there are 7000 species of edible vegetables; the second place is taken by Brazil, which has 3300; any Italian region has more plant species than any other state in the 'Europe."

"We have 58 thousand species of animals, ……The second country in the world is China which is 6% of the surface of the world and has 20,000. …..

This wonder is called biodiversity, we are the most biodiverse country in the world"

Northern versus Southern Italian cuisine

Italian cuisine is very regionalized, as Italy was unified only in the 19th century.

The cuisine of each province was based on local ingredients, history, and traditions.

So in the Southern region, we find a lot of Arab and Spanish ingredients, like fruits in savory dishes, almonds, pistachios, pine nuts, and very sweet desserts.

While Northern Italy had a stronger French, Austrian, German, and Hungarian influence, therefore a more recurrent use of butter, cream, and polenta.

After Italy's unification, many regional dishes traveled nationwide, and variations of traditional recipes were added to local Italian cuisine.

That is why for some recipes, it is difficult to talk about "A" (meaning only one) traditional Italian recipe as they may vary by different regions of Italy.

Regional variations versus worldwide variations

Popular Italian recipes have traveled worldwide and were adapted to different countries, costumes, and tastes.

Most often, these adaptations have entirely changed the pure spirit of Italian cuisine.

However, non-Italians have used the Italian regional variation to justify changes to the core recipe and still call it Italian.

This practice is misleading real Italian food lovers.

Italian cooking style is simple and made with good quality ingredients.

- There is never use of excessive garlic, a mix of too many flavors, or superfluous spices.

- We do not add cheese to seafood, chicken to pasta, pineapple to pizza, or Balsamic to Caprese.

- Adding cheese to a recipe doesn't make it Italian.

You can find out more about the authenticity of Italian food in the article: A Beginner’s Guide to Authentic Italian Food on the blog: Memorie di Angelina

The first Italian recipe book

Tuscany is the region where the Italian mother tongue was born.

Before the unification of Italy, each area had its own dialect, and starting from Dante Alighieri in the 14th century, Tuscan was proposed as a possible unified language.

Many more followed: Petrarca, Boccaccio, Macchiavelli and the Accademia della Crusca.

However, the Tuscan dialect was mainly used by scholars and aristocrats.

After the unification of Italy, the first book written in the Italian language was published, "The Betrothed" by Manzoni in 1827.

However, even if Manzoni was from Milan and spoke the Milanese dialect and French, he used the Tuscan dialect (specifically Florentine).

Therefore, he suggested to the Ministry of Education Broglio to introduce the Tuscan dialect in the school as the official Italian language.

During that same period, Pellegrino Artusi (from Tuscany) published a recipe book, "Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well" which became the first book of Italian cuisine written in Italian.

He published this book two decades after the unification of Italy, and for the first time, he included many traditional Italian recipes from all regions.

A historical look at Italian regional cuisine

While it would take an entire encyclopedia to cover all the Italian regional cuisines in detail, I will briefly describe each of the Italian regions, with more information on the most prominent ones.

I will also mention some of the most popular dishes you should try if traveling in the area and link them to the recipe if you want to try to cook them yourself.

Tuscany

Tuscan cuisine mixes the Etruscan simplicity's heritage and the Medici family's elaborate cuisine.

From the Crusades to the 13th century, Tuscan cuisine was rich in dips and spicy sauces to satisfy soldiers and lord-lings.

So, for example, during the middle ages, wild meat was cooked in a sweet and sour sauce made with raisins, almonds, vinegar, honey, ginger, and grape must.

When the chocolate arrived from America, it was added to the recipe Wild Boar With Chocolate published in Artusi's book.

Why Tuscan crusty bread has no salt

During the Middle Ages, bread was the main component of Tuscan food.

It was never thrown away.

Many Tuscan recipes are made with stale bread or breadcrumbs like the Ribbollita, Panzanella, Pappa al Pomodoro.

There was a rivalry between Pisa and Firenze and the Pisani boycotted the salt delivery to Florence.

This conflict is why Tuscan bread is traditionally made without salt and perfectly combines with rich and spicy sauces.

Tuscan is the origin of French cuisine

Tuscan cuisine became more refined with the influence of the Medici family.

During the Italian Renascence, banquettes were organized by aristocratic families as a sign of culture and sophistication.

The famous Bistecca alla Fiorentina, a Tbone beef steak, originates during the San Lorenzo feast on the 10th of august.

A large amount of beef was cooked over a large open fire and distributed to the population.

A lot of effort was put into organizing lavish feasts, developing more delicate recipes, table etiquette, and manners.

Caterina dei Medici brought Tuscan cuisine to the French court when she married Henri D'Orleans, second son to the French king.

Although cultured and refined, she was not good-looking and survived her husband's betrayals through her passion for food.

She brought a team of expert chefs and taught sophistication and table manners to the French court, which was still rudimentary from Middle Ages traditions.

New ingredients from the Americas

During this period, spices were used to add a unique flavor to dishes.

The United States introduced new ingredients: corn, potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, and turkeys.

Butter and cream substituted lard and cheese started to be more popular.

After the French revolution and the decline of the Medici family, Tuscan cuisine rebuilt its links to the countryside and its produce.

Recipes became sober and strictly linked to seasonal ingredients: "cucina povera degna di un re" simple cooking fit for a king.

Some traditional Tuscan recipes

14 dishes you need to try in Tuscany:

- Gnudi or Malfatti: ricotta gnocchi

- Pappardelle alla lepre: fresh pasta with hare stew

- Minestrone Toscano: vegetable soup with white beans and small maccheroncini

- Tortino di carciofi: artichokes frittata

- Bistecca alla Fiorentina: Tbone steak

- Fegatelli di Maiale alla Toscana: pig liver skewers on the open fire

- Pollo alla diavola: chicken on the barbecue

- Lepre in dolce e forte: Hare in sweet, strong sauce

- Bomboloni: fried donuts

- Castagnaccio: chestnut flour cake

- Cenci: fried cookies also called frappe or chiacchiere

- Panforte: dried fruits and nuts cake

- Ricciarelle: almonds cookies

- Zuccotto: a round dome cake

If you are traveling to Tuscany you may be interested in this article: 15 Best Places to Visit in Tuscany, Italy!

Emilia Romagna

Pellegrino Artusi (1820-1911) in his book: "Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well" writes: «Quando incontrate la cucina emiliana, fate una riverenza, perché se la merita». When you meet Emilian cuisine, make a curtsy because it deserves it.

Emilia Romagna is the region south of the Po valley, a very fertile land famous for its refined cuisine linked to the extravagance of the aristocratic families.

Traditional recipes from this region are opulent and sumptuous, consistent with the court's lavish lifestyle.

Pork Meat

Pork has been farmed in this region for a long time.

Traces of pig farms were found one thousand years before Christ: inside an Abbey, a mosaic reveals the killing of a pig, and documents confirm that in the 9th century, the monks were breading up to 4000 pigs.

Famous is the prosciutto di Parma, Parma ham.

The production is based in a specific zone where the sea breeze favors the ham's long maturation.

It was during 1511 when Pope Julius II besieged the city of Mirandola, and as the food was scarce, the population started using parts of the pig that were thrown out before then.

They started using the rind and the feet, inventing what is now called Cotechino, traditionally eaten every first day of the year.

Cheese

Another famous product from the region is the Parmigiano Reggiano (Parmesan Cheese). There has been a heated debate about the origin of the cheese, born in the Reggio region.

However, as the region's commercial center was in Parma, the cheese was earlier called only Parmigiano.

The name has since changed to Parmigiano Reggiano, making everyone happy.

Tagliatelle and Tortellini

The pride of the region is the fresh homemade pasta as wheat, and durum wheat flour is farmed and produced in its fertile fields of the Po valley.

Tagliatelle, lasagne, tortellini, and ravioli are creations that require long and elaborate preparations.

Each region town has its own specialty and fillings: Ferrara uses squash and cheese, Modena has various roasted meat, Bologna, the famous tortellini, Piacenza ricotta cheese, and herbs.

No wonder the famous chef Massimo Bottura and its restaurant Osteria Francescana, 3 Michelin stars and listed in the top 5 at The World's 50 Best Restaurants Awards since 2010, is based in this region in the city of Modena.

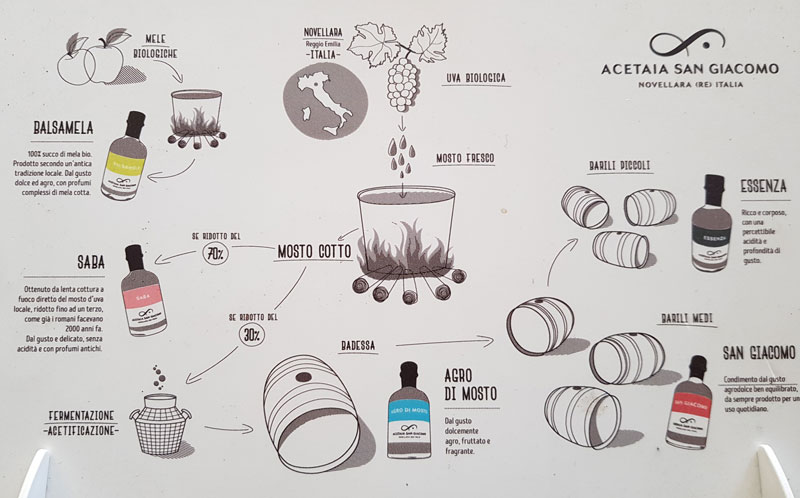

Modena is where the renowned Balsamic red wine vinegar originates.

Traditional Emilia Romagna recipes

19 dishes you should try in Emilia Romagna:

- Piadina Romagnola: flat bread

- Homemade pasta: pasta fresca all' uovo: Tagliatelle, Lasagne

- Anolini, cappellette, tortellini, ravioli

- Potato gnocchi

- Gnocco fritto: fried dough

- Maccheroni, malfatti

- Pasticcio: baked casserole made with tagliatelle, maccheroni tortellini

- Parmesan risotto

- Rotolo ripieno: stuffed bread rolls

- Ragu alla Bolognese: meat sauce

- Arrosto ripieno: stuffed roast beef

- Cotechino: large sausage using the rind and the feet of the pig

- Cappone ripieno: capon stuffed with veal, pork and ham

- Pollo alla cacciatore: chicken stew

- Stracotto: beef stew

- Castagnole: fried donuts

- Crostata Emiliana: jam tart

- Migliaccio: tart filled with chocolate and pig blood

- Nocino: green walnuts liqueur

Veneto

Venetian cuisine is highly influenced by its geographic location, splendor, and prestige as a prominent merchant city throughout history.

Located in the Adriatic sea estuary lagoon of the Po valley, between fresh and seawater, its market stalls are copious with fish, seafood, and freshwater fish.

In 1591 Giulio Cesare De Solis writes: every day on the Venetian fishmongers' stalls, there is a large number of fish "that cannot be found in Rome and Naples put together in a whole month".

Fish, birds, and vegetables

Besides fishing, Venetian were also very skilled hunters of wild birds, developing hunting techniques that were unique to the Venetian lagoon's habitat.

Meat and fish were served with vegetables grown locally in the various lagoon islands and coastal lands.

The warm, humid climate and the salty air created fertile land.

Artichokes, asparagus, yellow squash, radicchio, peas, zucchini, beans, aubergines, peppers, fennels, and cabbages have the perfect habitat and grow in abundance.

Spices

Even if Venice was a wealthy state, its cuisine was always very simple and sober.

Venetian believed, and still do, that genuine fresh produce didn't need long elaboration that would otherwise distort their taste.

Venice has been, for centuries, the main door to international trade with the East.

In addition, cultural exchange and interaction have created a particular cuisine highly influenced by foreign commerce.

Compared to other Italian regional cuisines, the prominent use of spices has been one of the main characteristics of the traditional Venetian food: black pepper, red pepper flakes, raisins, ginger, saffron, nutmeg, cinnamon, and cloves.

The Venetians were good at marketing those spices to the rest of Europe as a status symbol, increasing demand, and creating a lucrative market for "Venetian" packed spices.

Their use was excessive, but luckily, they were scaled down to a more acceptable level with time.

Rice

Rice was also imported to Europe through Venice, and during the Middle Ages, it was so expensive that it was sold by counting each grain.

It was mainly used in small quantities to thicken soups and minestre.

During the 1500s, hinterlands were added to the Venetian state, and as rice was planted in those fields, it became an integral part of the Venetian diet.

Foreign influence

Venetian cuisine was also influenced by foreign merchants in the city, particularly Jews: rice with raisins, rice with vegetables, duck, goose, and the turkey was introduced to their diet.

Venetians love their desserts; the Crusades brought sugar to the region for the first time.

The family Corner bought entire sugar cane plantations between Cyprus and Crete, and the best-refined sugar was imported into Venice.

Famous are the sugar sculptures made even by well-known artists like Antonio Canova. They were exhibited during lavish banquets.

Conservation techniques

Venetians had to develop ways of preserving food during their shipments.

Learning many techniques from their trading partners, Venetians used hams, salami, sausage, and seafood stored in salt like anchovies, baccala', bottarga, and smoked fish.

As Venice was a city with many foreign merchants, its streets were and still are full of Osterie.

Osterie are taverns where travelers and locals would stop for a glass of white wine and a bite: Cicchetti, an assortment of aperitives including liver, spleen, nerves, half eggs with anchovies, omelets, artichokes, octopus, fried fish, cotechino with polenta.

Traditional Venetian recipes

13 dishes you need to try in Veneto:

- Pate di fegato: Liver pate'

- Pasta coi Bisi: pasta with peas

- Pasta e Fasioi: pasta with beans

- Risi e Bisi: risotto with peas

- Risotto nero: risotto with black ink cuttlefish

- Linguini al nero di seppia

- Baccala mantecato

- Grilled Radicchio

- Maiale al latte: pork cooked in milk

- Polenta e Osei: quails, larks or thrushes served with polenta

- Cerma fritta: fried custard

- Pandoro di Verona: a panettone without candied fruits and raisins

- Tiramisu

Piemonte

The term "Piemonte" first emerged in history during the latter half of the 13th century, coinciding with the establishment of the cuisine now recognized as Piemontese.

It was the period of the French Revolution when the longstanding societal structures of the regime were being uprooted.

During this time, much of Piedmontese cuisine began to take form.

Piedmontese chefs were among the first to challenge the French's claim to be the ultimate authority in gastronomy.

Instead, they established their autonomy and distinctive identity in the field.

The first anonymous recipe book appeared during this period: "The Piedmontese cook perfected in Paris" (Turin 1766).

The book was rich with precise instructions for preparing items such as jams, candied dishes, vinegar, oil, salt, and a wide range of frozen treats, syrups, flavored waters, and liqueurs.

These recipes were likely derived from earlier French cookbooks.

Through revitalizing Piedmontese cuisine, Italy regained a prestige lost since the Renaissance, when culinary excellence peaked.

However, this prestige began to wane following the marriage of Catherine de' Medici to the future king of France, Henry II, as French cuisine began to gain international recognition and popularity, culminating in its dominance until the fall of the Bastille.

Today the Piedimonte cuisine has acquired its own identity even if it still maintains some traditional French recipes like the Vitel Tonne, apple or pear charlottes (cooked fruit dessert), and candied chestnuts (marrons glacés).

Piedmontese cuisine is characterized by the abundant use of butter and lard, the consumption of raw vegetables, the use of Sanato (veal a few months old fed only with milk), the choice of cheeses, the extensive use of truffles, the preparation of breadsticks and the careful use of garlic (bagna cauda), la farinata, il "bollito" (boiled beef and veal), il antipasto fritto (fried appetizers).

The reclamation of the swampy lands made by the Cistercian monks at the end of the Middle Ages led to the intensive cultivation of rice.

Piedmont remains the most significant European production area, and rice is essential in its cuisine.

Val d'Aosta

The cuisine of the wealthy Aosta valley has been diverse, drawing influences from various gastronomic traditions, including Roman, Savoyard (since the 11th century), French, and Swiss cuisines.

The Roman legions that occupied the Valle d'Aosta region brought with them culinary practices centered around hunting and the use of barley in soups.

However, the local population's diet primarily consists of vegetables, cabbage, rye bread, and a few varieties of cheese.

In this region, pork has historically been used to make salami, sausages, lard, and black pudding, which were crucial for winter survival.

In addition, this area has a long tradition of livestock farming and dairy production.

It has been renowned for its cheese since the Middle Ages, with fontina being a particularly iconic example.

Traditional Piemonte and Val d'Aosta recipes

16 dishes you should try in Piemonto and Val D' Aosta:

- Bagna Caoda: anchovies and garlic dipping sauce

- Fondua: Cheese fondu with white truffle

- Vitello tonne': poached veal in wine seasoned with a tuna sauce

- Angolotti, cannelloni: made with fresh pasta

- Gnocchi: potato and flour

- Polenta alla Piemontese: with leftover roasted meat

- Torta verde: Easter spinach tart

- Cavolo farcito: cabbage stuffed with meat

- Bollito misto: boiled meat stew

- Brasato al Barolo: beef stew in wine

- Fritto misto: veal brain, pork liver, chicken nuggets, lamb chops, eggplants, zucchini, flower blossom, Semolino, mushrooms, trout, frog

- Lepre in salmi: hare stew

- Baci di Dama, Brutti ma buoni and Amaretti: almond cookies

- Budino: pudding

- Torta al gianduia, nutella

- Zabaione: marsala custard

Friuli Venezia Giulia

Located north of Veneto, the cuisine of this region is distinguished by the blend of rustic peasant customs with those of the aristocracy, which were adopted during the rule of the Serenissima and the Habsburgs.

The widespread use of sugar, butter, fruit, cheeses, jams, and mustards characterizes Friulian cuisine.

The geography of this area developed a cuisine rich in seafood, but the main ingredient of the region is Polenta.

Friulian Polenta is made with corn abundantly produced in the region.

It is firm, well-cooked, and goes well with cheese (Polenta Concia), mushrooms, and white truffles.

A large variety of cow's milk cheeses (sheep are scarce) take the name of the locality where they are produced.

Throughout the region's cuisine, pork has always held a significant role, with particular attention given to preparing cured meats, such as San Daniele ham.

Additionally, the Hungarian dish of goulash has become widely popular throughout the area.

Traditional Friuli Venezia Giulia recipes

9 dishes you should try if you are in Fruili Venezia Giulia:

- Cialzon: ravioli filled with apples, ricotta cheese, boiled potatoes, pears, raisins, spinach, pine nuts, cinnamon and cocoa.

- Jota: Soup made from sauerkraut, beans and potatoes

- Boretto di pesce: fish soup

- Baccala alla cappuccina: with anchovies, raisins, cinnamon and sugar

- Tuna stored in olive oil

- Gulasch Triestino

- Polenta concia: with cheese

- Crostata di Mandorle: almond crostata

- Gubana: leavened sweet dough filled with raisins, walnuts, pine nuts, sugar and grappa

Trentino Alto Adige

Although both regions are connected by their proximity and sisterhood, the cuisine of Trentino and Alto Adige should be regarded as distinct entities.

Trento's gastronomic legacy is comprised of survival cuisine and lavish banquets that date back to the time of the Council.

Conversely, Bolzano, the gateway to the Dolomites, represents a crossroads where the culinary traditions of Austria, Germany, and Hungary converge.

Until a few years ago, it was difficult to find pasta dishes.

Despite having shared the Habsburg domain for a long time, the two provinces have absorbed its culture differently.

Trentino

The peasant population of this region had a diet consisting of Polenta (made from corn, potatoes, or buckwheat), sauerkraut (derived from thinly sliced cabbage preserved in salt), lard, minestrone, and small amounts of cheese and butter.

In contrast, the wealthy prelate and powerful people consumed above all meat from the Alps, as Platina testifies to us (15th century).

The "pasticcio di macaroni" is a dish of great extravagance, still served today on special occasions.

During banquets, the most opulent dishes were those made from game, which included birds such as capercaillie and woodland animals like fallow deer, chamois, and roe deer, cooked over coals.

However, these meats were also frequently combined with butter, cheese, and milk, as seen in the ancient recipe for the "hunting leg."

But the courts also appreciated poor foods, like barley soup, which is still a typical dish today.

Only in the 1800s, following the annexation of this land to the Kingdom of Italy, was Trentino cuisine enriched with pasta, which has always been replaced with "canederli" and various gnocchi.

Alto Adige

South Tyrolean cuisine has its roots in German culinary practices, evident in the preparation methods, flavor combinations of sugar and salt, use of spices, and preference for ingredients like potatoes, rye, barley, and cabbage.

The cuisine also shows influences from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as seen in dishes like "goulash."

However, one of the most popular dishes in the region is "knödel," which is prepared in various ways, with rye bread, liver, or speck being the most common ingredients.

Traditional Trentino Alto Adige recipes

8 dishes to try if you are in Trentino Alto Adige:

- Smacafam: soft focaccia with sausage

- Stranglolapreti: gnocchi made with Swiss chard, bread crumbs

- Canederli: bread dumpling cooked in broth

- Spatzle: small irregular dumplings of flour, milk and eggs, also green (spinach) or red (beetroot)

- Tortini di patate: potato frittes

- Polenta e capus: polenta and cabbage

- Strudel: apple

- Zelten: Christmas cake with candied fruits and nuts

Lombardia

Lombardy cuisine cannot be characterized as a single entity, as its provinces have various culinary traditions, with neighboring regions exerting influence.

The cuisine in the plains area is distinct from that in the pre-Alpine and Alpine areas.

However, there are still common elements in the cuisine of Lombard provinces, such as a preference for butter over oil, rice over pasta, and the widespread production of cheeses and dairy products.

Milano is famous for its recipes of risotto alla Milanese with saffron, Osso buco, veal cotoletta and Panettone.

The best of the mountain repertoire is offered by Valtellina, which has its emblem in pizzoccheri a type of pasta made from a mixture of buckwheat flour and other flours, resembling tagliatelle, but with a grayish hue.

They are served with potatoes, melted cheese, cabbage and seasoned with butter and garlic.

In Mantua, you can find typical Emilian stuffed pasta, risotto with Lombard root, medieval court dishes and desserts such as sbrisolona.

Cremona is known for its mustard and Torrone nougat and for the opulence of its "mixed boiled meats".

Traditional Lombardia recipes

12 dishes you should try if you are in Lombardia:

- Casonsei: ravioli filled with sausage

- Cassoeùla: pork stew with cabbage

- Malfatti: spinach and ricotta gnocchi

- Pizzoccheri: buckwheat flour pasta served with potatoes, cheese and cabbage

- Risotto alla milanese: risotto with saffron

- Cotoletta alla Milanese; fried breaded veal

- Osso buco with beef marrow

- Brasato: beef stew

- Polenta Taragna: polenta butter and cheese

- Colomba Pasquale

- Panettone

- Torrone: Italian nougat

Liguria

Liguria cuisine is very simple, mainly made with herbs and local vegetables.

Liguria is located between the Mediterranean sea and the Alps, and its microclimate is perfect for flourishing vegetables, fruits, wild mushrooms, and wild herbs.

Herbs

Pra', just outside Genova, is famous for the quality of its basil. Pesto alla Genovese originated here.

Also, tart fillings are usually made with herbs and cheese, and tortelli are filled with wild herb Borage.

Merchant City

Like Venice, Genova is also a harbor town; its cuisine is highly influenced by its trade.

Here we also find baccala' and stockfish, a way to preserve fish learned from the trade with Norwegian.

During the Italian Renaissance, the region was populated by various shops, and its chefs were sought after by the numerous lordships.

Still today, there are many similarities between Ligurian, Provencal, Catalan, and Portuguese cuisine.

Ligurian cuisine is generally simple and made with inexpensive ingredients, homegrown vegetables, flour derivatives, olive oil, and local seafood.

Traditional Ligurian recipes

10 dishes you need to try if you are in Liguria:

- Farinata: chickpeas pancake

- Torta pasqualina: tart with ricotta and swiss chard

- Trofie al pesto alla Genovese

- Pansoti: herbs ravioli

- Focaccia alla genovese

- Piscialandrea: in French pissaladiere pizza with onions and anchiovis

- Mesciua: chickpeas and bean stew

- Stoccafisso

- Canestrelli biscuits

- Pandolce Genovese

Sardegna

Over the centuries, Sardinian cuisine has retained its well-defined and distinct characteristics, partly due to its geographical isolation as an island.

It continues to preserve its prehistoric culinary knowledge in its original form, enriched and refined by the influence of the dominant population, such as the Phoenicians, Punics, Romans, Genoese, Pisans, Catalans, Spanish, and Piedmontese.

The pastoral tradition is deeply ingrained in this region, resulting in a remarkable variety of typical products.

These foods have emerged due to the availability of raw materials linked to sheep farming, as well as the need to sustain oneself during extended periods away from home without the ability to prepare complex meals.

The cuisine that has arisen from this tradition is often considered "poor," yet it remains equally refined.

The scarcity of ingredients resulted in imaginative and flavorful dishes with what is available.

The Sardinian cheese is famous like Pecorino Sardo (stronger than the pecorino Romano), the ricotta, caseggiou (small provole) and the Fresa, soft, buttery, creamy cheese.

Well known also the bread "Carta da musica" a thin, crumbly bread (no yeast) the shepherd brings with him so it doesn't become stale.

It is a cuisine characterized by its seasonality with the main activities of pastoralism, agriculture, fishing, foraging, and hunting.

Traditional Sardinian recipes

10 dishes to try when you are in Sardegna

- Pane Carasau: or music card a thin, crumbly bread

- Gnocchetti sardi: chunky pasta

- Culigiones: ravioli filled with potatoes and Pecorino sardo

- Sa Fregula: couscous with cockles

- Stuffed zucchini with meat

- Porceddu: pork cooked on the spit

- Burrida: catfish boiled and marinated in a walnut sauce

- Sas seattas: fried sweet ravioli

- Papassinus: shortbread biscuits and sultanas

- Saranzada: candied orange peel

Umbria

Much of Umbria was under the influence of the Etruscan civilization and then of the Roman one, thus developing a cuisine based on the consumption of olive oil, legumes (lentil) and cereals (spelt).

During the Middle Ages, Umbria became increasingly connected to the Papal court, with the church promoting the establishment of monasteries, abbeys, and religious orders throughout the region.

San Francesco, San Benedetto, Santa Chiara, and Santa Rita are some of the immortal saints who lived there during this period.

As a result, Umbrian cuisine became centered around the traditions and monastic calendar.

Norcia has been famous since Roman times for the breeding of pigs, the famous "black" of the Valnerina, with the production of extraordinary hams, loin, sausages, budellucci, and porchetta.

The lambs from San Benedetto and the kids (young goat) of Cascia are highly appreciated, while the production of caci and caciotte is exalted in the medieval junkets and the "castaldo" (sheep's or cow's milk cheese with the addition of white truffle).

In addition to games such as pigeons and wild boars, the Umbrians have a cuisine rich in freshwater fish such as tench, eels, carp, perch, and trout.

But the Umbrian region is specifically famous for its truffles: in Norcia and Spoleto "the diamond of the kitchen" represents an indispensable economic wealth.

Both the "tuber melanosporum" king of Umbrian cuisine, and the scorzone (less fragrant summer truffle) are included in recipes of all kinds, from appetizers to desserts.

Traditional Umbrian recipes

11 dishes to try if you are in Umbria:

- Arvortolo: fried pizza dough

- Focaccia Umbra

- Lentil soup

- Strangozzi fresh fettuccine pasta without eggs

- Torta di Pasqua: Easter tart with cheese

- Mazzafegato: pork liver salami

- Porchetta or Cicotto roasted pork

- Pollo alla Cacciatore: chicken stew in tomato sauce

- Brosega: eggs cooked in tomato sauce

- Brustengolo: polenta cake

- Pinoccate: pinenut candies

Lazio

Lazio cuisine is largely represented by Roman cuisine. Having lost the glories of Ancient Rome, where it was possible to eat any delicacy of the civilized world, contemporary Roman gastronomy is now represented by four different components:

1) Jewish (called "giudea"), the most refined, ingenious and cultured, to which we owe famous dishes such as "carciofi alla giudia" or "anchovies with envy";

2) Burina, of Abruzzo origin, which brought, among other things, the "bucatini all'amatriciana", the "pasta alla carbonara", the lamb Abbacchio and pork Porchetta dishes;

3) butcher, born around the slaughterhouses using cheap cuts, i.e. entrails, legs, cheek, "rigatoni con la paiata", "trippa di manzo alla romana" or the "coda alla vaccinara".

4) Vegetables from the agriculture of the surrounding areas: among the vegetables, artichokes, red peppers, and salads like puntarelle

Rome, the capital city

Rome is the town where I grew up, and I have way too much information I would like to share with you.

Writing only a section of this article would be too constrained.

The history of Roman cuisine is so broad, rich, and complex that it deserves a dedicated article, if not more.

I have already written two articles dedicated to different aspects of food during the roman times.

So you can read more about Roman cuisine in the articles:

- The Amazing Trajan’s Ancient Roman Markets

- The Fascinating Ancient Roman Food And Recipes

- A Historic Walk Through The Charm Of Romans Market

Traditional Lazio recipes

19 dishes to try if you are in Lazio or Rome

- Pizza al taglio

- Suppli: rice cake

- Gnocchi alla Romana

- Pagliata con Rigatoni: pasta seasoned with the uppermost part of the milk calf's intestines

- Spaghetti Cacio e pepe

- Spaghetti alla Carbonara

- Spaghetti alla Matriciana

- Spaghetti alle vongole

- Carciofi alla Giudia

- Carciofi alla Romana: roman Artichokes

- Puntarelle alla Romana

- Agretti

- Tomato stuffed with rice

- Stuffed zucchine

- Abbacchio alla Romana: lamb baked in wine and vinegar

- Coda alla Vaccinara: oxtail

- Trippa di Trastevere: tripe

- Maritozzi: sweet bread filled with whipped cream

- Pizza di polenta: polenta cake

Abruzzo

The ruggedness of the mountain ranges surrounding Abruzzo has allowed the region's culinary art to remain vibrant and independent.

However, for many centuries, the local economy struggled to survive, as neither agriculture (which was not very profitable in the highest Apennines) nor pastoralism provided prosperity.

The lack of prominent families with their lavish banquets has resulted in the absence of Abruzzo recipes from the most well-known gastronomic treatises of various centuries.

However, chili pepper is constantly in all the region's dishes.

Interestingly, saffron - which has its Italian origins in Abruzzo - is not frequently used in local cuisine.

Durum wheat is a local produce used to make the most famous pasta recipe in maccheroni alla chitarra.

Although, the preparations of the shepherds heavily influence the gastronomy of Abruzzo, the cheeses and sheep meat are important: typical are the lamb a "catturo", the "capra alla neratese", or the "arrosticini" (roasted sheep meat skewers ).

In the coastal areas, one can taste the flavors of the sea, including oily fish, mollusks, and crustaceans. The region is also renowned for its small, red mullets, known as "agostinelle."

Other notable dishes include stuffed cuttlefish and a variety of soups, each representing a local variation of the Adriatic fish soup.

The tradition in Abruzzo of commemorating special occasions with endless lunches led to the creation of "panarde," extravagant celebrations that provided a reprieve from daily hardship.

Respectable wedding dinners could not consist of fewer than twenty courses, and those offered to special guests included up to thirty.

Those who could not withstand the temptation to sample such an abundance of food risked offending the table host irreparably.

Molise

The cuisine of Molise is characterized by the simplicity of its preparations and the use of authentic ingredients.

Nonetheless, there is a noticeable contrast between the dishes prepared in the inland regions, which rely on homemade pasta and mainly feature kid or lamb meat and those created along the narrow coastal strip, where fish takes center stage.

In addition to the different varieties of fresh pasta, among the first courses, we point out the Polenta, present throughout the territory, seasoned above all with rich pork or lamb sauces

Traditional Abruzzo and Molise recipes

7 dishes to try if you are in Abruzzo or Molise:

- Bruschetta

- Grilled scamorze

- Maccheroni alla chitarra

- Spaghetti Algio, oilio e peperoncino

- Stuffed artichokes

- Arrosticini

- Chocolate Torrone

Marche

Marche is a confederation of flavors.

The north's gastronomic uses are closely related to those of the neighboring Romagna (soups), and those of Abruzzo largely influence the dishes in the south.

Mushrooms, olives, and truffles dominate the peasant aspect of the Marche cuisine.

One-third of the entire Italian annual production is concentrated in this region.

The gastronomy of the Marches has a natural taste in stuffed foods, one of the most representative dishes in stuffed olives Ascolane.

The main dishes of the hinterland are based on pork, delicious porchetta, and Cotechino.

Many vegetables are almost omnipresent in this kitchen, such as tomatoes, fresh or preserved, peppers, broccoli, celery, and fennel,

Traditional Marche recipes

8 dishes you should try if you go to Marche:

- Olive ascolane: stuffed fried olives

- Crema fritta: Fried custard

- Ciauscolo spreadable salami

- Ciavarro: pulse soup

- Vincisgrassi: a local lasagna

- Calcioni: ravioli filled with of ricotta, pecorino, lemon zest and marjoram

- Brodetto marchigiano: seafood stew

- Calcioni: Sweet cheese ravioli

Campania

The fertile volcanic soil of the region around Naples made the area the closer and leading food supplier to the capital during the Roman Empire.

Due to its historical background, Naples's cuisine was influenced by the refined habits of the Islamic courts with the Angioini and Spanish and French from the Borboni as well as the peasant food reserved for the poor population.

Aristocratic cuisine

From the Middle East, they learned the abundant spices, mixing of flavors, such as raisins, pine nuts, sugar, and vinegar, and the technique of boiling the meat before final cooking.

This last one originates Napolean ragu, where the meat is cooked in tomato sauce and used to make many dishes, including the famous Lasagne di Carnevale.

With the Borbon in the 18th century, the fame of French cuisine arrived in Naples.

Maria Carolina of Austria, the wife of Ferdinando IV di Borbone, king of Naples and Sicily, had a passion for French cuisine and hired French chefs to prepare the meals at the palace.

Soon the aristocracy followed the trend, and many French chefs moved to Naples to cook for the local nobility and wealthy families.

The cuisine in the South of Italy was already rich with delicious local produce from the warm and fertile land.

Neapolitan cuisine became a sophisticated combination of French techniques and Southern ingredients.

The fertile volcanic soil, the strong southern sun, and the breeze from the sea give its fruits and vegetables unique sweetness and outstanding flavors.

Many Neapolitan recipes were called with French names adapted to local dialects like Ragu', Sartu', Gatto': complicated casseroles of lasagna noodles, mashed potatoes, eggplants, or red peppers stuffed with chicken livers, sausages, meatballs, etc.

A special name was also given to the French chefs working for the most wealthy families: Monsu', an adapted pronunciation of the French word: monsieur.

Monsu' were regarded as celebrities and had fame and recognition.

In the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (which includes the entire South of Italy), those Monsu' created many recipes using local ingredients and passed those creations and love for food to future generation.

Cucina Povera: peasant cuisine

The food reserved for the poor population was based on local produces, cheese, pulses, and rarely meat.

Not until the 19th century, when Agnoletti and Cavalcanti published their works, did the cuisine of the less affluent start to be acknowledged.

The first written trace of Mozzarella cheese was found in the Episcopal Archive of Capua going back to the 12th century: "a mozza or provatura with a piece of bread was the service that the monks of the monastery of S. Lorenzo in Capua gave to the pilgrims who every year for ancient tradition went in procession to that Church".

Tomatoes became an essential ingredient in Neapolitan cuisine, used in ragù, casseroles, or Neapolitan pizza.

It has been said: "in Naples, the tomato is half a religion."

An essential part of Neapolitan cuisine is the street food sold in kiosks or stalls and consumed at any time of the day, like fried pizza, crocchè di patate, fried seafood and calamari, pizzette, tartine e frittelle.

Traditional Campania recipes

25 dishes you need to try if you go to Naples or Campania:

- Calzone

- Pizza

- Pizza fritta: fried pizza

- Pizza campofranco: focaccia

- Pizza rustica: tart with cheese and ham

- Gatto: potato pie

- Fried mozzarella

- Mozzarella in Carrozza

- Panzerotti

- Taralli

- Tortano cu cicoli o Casatiello: savory pie with pork rinds

- Lasagne di Carnevale

- Sartu': rice timbal

- Pasta a frittata: fried pasta

- Macheroni timbal

- Napoletan ragu

- Salsa al pomodoro: tomato sauce

- Salsa Genovese

- 'Mpepata di Cozze: mussles

- Insalata di rinforzo: salad with cauliflour

- Peperoni imbottiti: stuffed peppers

- Pastiera Napoletana

- Pasta frolla Napoletana: with almonds

- Sfogliatelle

- Struffoli

- Zeppole di Carnevale: fried donut Graffe

Basilicata

From a gastronomic point of view, Basilicata is greatly influenced by the neighboring regions.

Its cuisine is poor and based on the earth's products, meat and dairy products deriving from sheep farms and pork.

The art of preserving food has always been practiced here, and the lack of courts and rich banquets has limited the panorama of culinary art.

Among the products obtained from the pig, the most famous, since ancient Rome, is the sausage or lucanica, obtained from the pig of the region, generally lean because it grazes on the mountains together with sheep and lambs.

Traditional Basilicata recipes

6 dishes you need to try if you are in Basilicata:

- Strangulapreti fresh pasta

- Baccala and potatoes

- Ciammotta: vegetable stew

- Pignata: mutton or lamb cut into pieces, potatoes and cherry tomatoes

- Torta di ricotta: ricotta tart

- Fried Strangolapreti

Puglia

At the southernmost point of the Italian peninsula, Apulia forms the heel of the country's distinctive boot shape.

The region has a rich and diverse history, being part of the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

As a result, its territory encompasses various landscapes and cultures, drawing influences from multiple sources, including Roman, Byzantine, Messapian, and Greek traditions.

A simple selection of ingredients like durum wheat, oil, vegetables, fish, and wine characterizes Apulian cuisine.

Wheat is a versatile ingredient that forms the basis of many Apulian dishes, including bread, pasta, rustic pizzas, and calzones.

The humble dishes of this region are perfect for a vegetarian or vegan diet, as butter was almost unused, and the meat was eaten only on Sundays.

Its handmade pasta seasoned with vegetables is renowned like Orecchiette, Cavatelli with broccoli, pasta and cabbage, macaroni and aubergines, pasta and bean purée, spaghetti, and chicory.

Traditionally, beef is scarcely used in Apulia, while game, poultry, pigs, wild rabbits, and above all, sheep meat are widely used.

Traditional Apuglia recipes

12 dishes you should try if you are in Puglia:

- Frisedda: biscuit bread

- Torta rustica or Sfogliata:

- Cavateddi con Broccoli

- Orecchiette con cime di rape: broccoli rabe

- Seafood spaghetti

- Polpi in umido: small octopus stew

- Stuffed calamari

- Peppers spiedini

- Stuffed eggplants

- Zucchini parmigiana

- Carteddate e purciduzzi: fried dough shaped like a rose

- Bocconotti

Calabria

During historical times, Calabria thrived as a center of civilization and attracted Greek immigrants, Magna Grecia.

As a result, traditional Calabrian cuisine is deeply rooted in its customs, beliefs, and history, with many recipes dating back to the early days of Mediterranean culture.

Some dishes were influenced by the culinary practices of the Greeks and Latins, while the Arabs, Normans, Spanish, and French introduced others.

For instance, the Achaean colony of "Sybaris" (Sibari) was renowned for its luxurious lifestyle, and the "laganon" (large noodles) was among the favorite foods enjoyed by its inhabitants, as later noted by Apicius in the first cooking book during the Roman Empire "De Re Coquinaria".

"Mustica" is a mouthwatering dish of Arab origin that involves preserving freshly caught anchovies in oil, with modern recipes often featuring chili peppers as well.

This traditional food has been a crucial resource for Apennine villages, where the ability to store non-perishable provisions was once the most prized form of wealth.

During the famine, southern Italians relied on preserved sausages, suet, cheese, aubergines in oil, and dried tomatoes to ensure their survival.

All the main ingredients that form the basis of the cuisine of the ancient "Brutium" (Latin name of Calabria), vegetables, pasta, pork derivatives, and fish on the coast, are personalized by the contribution of chili pepper and olive oil, practically present in almost all the dishes of the area.

Traditional Calabrese recipes

- Nduja: spreadable spicy salami

- Pitta: ciambella bread

- Sardella or 'nannata: newborn sardines frittes

- Morzello: tripe sandwich

- Frittola: pork cracklings

- Fileja: long and curved durum wheat pasta

- Pasta ca’ muddica: pasta with breadcrumbs

- Baked swordfish braciolette

- Meat braciolette:

- Eggplant Parmigiana

- Stocaffisso with potatoes, peppers and tomato

- Pipi chini: stuffed peppers

- Fried eggplant balls

- Uova alla Monachella: fried bredded boiled eggs

- Peperonata: pepper stew

- Cuzzupa o cudduraci: Easter cookies

- Pitta ‘mpigliata: twisted puff pastry richly spiced and filled with dried fruit

- Scaudet: chestnuts ciambelle

- Scalille o scaledde

Sicily

Sicilian cuisine has ancient roots in the Magna Graecia civilization 8th century BC.

Their diets were based on fruits, vegetables, herbs, seafood, and olive oil.

The exceptional combination of the fertile volcanic soil, the sea, and the hills created the perfect habit to grow outstanding produce like in Naples.

Arabs arrived in Sicily in the 8th century AC, introducing sugar cane, rice, jasmine, cotton, anise, sesame, cinnamon, and saffron.

That is why we often find in Sicilian cuisine sweet in savory dishes like raisins in meatballs, orange salad, and roasted pepper in a sweet-sour sauce.

Many Sicilian desserts like torrone, cassata, and sorbetto were developed from Arab ingredients and influence.

Almonds and pistachios are grown locally and appear in many sweet and savory recipes.

Also, in Sicily, we find the baccala' and stocafisso like in Liguria and Venice, Northern recipes brought by the Norman invasion.

After the Norman, Sicily was invaded by the French and the Spanish.

During this period, Sicilians started to create more complex recipes like the Braciola, Caponata, stuffed calamari, pasta con le sarde, baked swordfish, sarde e beccafico, sfinciuni.

We find many recipes in Camilleri's books and TV series: Il Commissario Montalbano.

New ingredients were introduced from America: chili, peppers, potatoes and turkey, and eggplants from the Indies.

Especially eggplants took over in the region around Catania as they grew abundant in the fertile volcanic soil of Etna.

Every recipe where eggplants are added is called alla Norma: pasta, arancini, pizza, timbal, swordfish ragu.

During the Italian Renaissance, the Sicilian baronial families contributed to enriching Sicilian cuisine.

As in Naples, we find the Monsu', French chefs cooking for the noble families.

So we have introduced more complex seafood recipes with swordfish, Arancini and Timballi.

Local girls would help those chefs in the kitchen, learning the art of cooking.

Going back home, those girls cook those dishes for their families using less expensive ingredients.

So for every sumptuous Sicilian dish, you will find a version for wealthy families and one for farmers.

Traditional Sicilian recipes

23 dishes you need to try if you are in Sicily:

- Arancini di riso

- Panelle: fried chickpeas pancakes

- Salmoriglio: seasoning for seafood

- Pasta con le sarde

- Pasta fritta

- Sfincione

- Pani câ meusa

- Pasta alla Norma

- Timballo di maccheroni

- Swordfish Braciole

- Cuscusu

- Caponata

- Peperonata

- Polpettone siciliano: meatloaf

- Pork Scaloppine with Marsala

- Cannoli

- Cassata Sicilian

- Pasta di mandorle

- Pignolata

- Granita

- Sorbetto

- Gelato

- Brioscia

More authentic Italian resources

If you are interested in learning more about Italian cooking, check out the article 77 traditional Italian ingredients and best brands with links to my favorite brands and a printable shopping list.

For more information you can read: , 36 Essential Herbs And Spices Used In Italian Cooking, 32 most popular Italian street food, 22 Italian breakfast recipes, Italian Sunday dinner a 6 meal courses, Italian table setting and etiquette

Find my recommendations of authentic Italian cooking books translated into English in my Amazon shop section: Cooking Books

Hope you find this article about traditional Italian recipes helpful, please if you have any questions, write them in the comments below and I will be happy to respond and help. For more information, you can visit the category: Italian food traditions. You can find delicious ideas if you FOLLOW ME on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest and Instagram or sign up to my newsletter.

Leave a Reply